Karamoja is known for its seasonal rivers. They flood during the rainy season but completely dry up when the rains cease. Due to the mountainous rocky terrain of the Region, the floods can be quite violent, many times washing away bridges and homes. The water flows down from the steep mountains, gaining speed as it approaches the low lands carrying rocks and huge boulders with it. When the rains cease and the rivers dry, huge rocks are left lying along the river path, along with all the sand and soil that is washed from upstream which contain one important item: gold!

As the water tumbles down through the mountains to the low lands, it passes by several gold mining and processing centres. Water is a critical ingredient for any gold miner and therefore many gold mining and processing sites are strategically located near rivers for easy access to water. The waste that is disposed into the river by these sites is carried downstream along with the sand and rocks and deposited along the river bed as the river dries up. It is here that the locals come in.

At Chepkararat village, Lokales Parish, Karita sub-county in Amudat District, locals have long survived on the gold in the sands of the Chepkararat river bed. Grace Rotich, a 39-year old mother of six, has eked a living from these sands for years. The entire family works here. Her husband and early teenag son dig up the riverbeds and pass on the sand to her for panning-a process where water is passed over the sands, draining it of soils and small stones, in order to expose the gold particles. Gold is a heavy metal and tends to stay at the bottom of the solution when water is added to the sand.

I found Grace at work in the blistering afternoon heat. Karamoja sun can be unforgiving, but this family has to stand the heat in order to feed. Her less than one year daughter is sleeping under a tree, while two of her older siblings tend to her.

I ask her if she has found any gold. With a smile, she brings the metallic pan closer to my face and shows me two miniscule particles, one shiny silver in colour and the other yellowish brown. That is her catch for the day. Two tiny pebbles of gold. She explains that the silver one has mercury in it and she will have to burn it when she gets home to remove the mercury. This leaves me wondering how much of the gold then will be left.

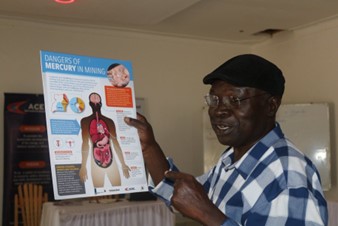

“People up (stream) use mercury, it comes down with the water and sand. We pick it then burn it at home,” says Grace, oblivious of the dangers of burning mercury in her house to her life and family. The processing sites upstream the river use mercury to trap gold and dispose the waste into the river.

I ask her whether she has found joy in this gold hunt and her answer is even more interesting. According to the miners here, gold money should not be saved or invested. All the daily earnings must be spent that very day or else the miner will not find any gold the following day. The gold will “hide” she says.

“I don’t call it money,” she explains. “Money we get today, we eat today. When you save the money, tomorrow you will not get gold. I don’t know who made this gold,” she adds in seeming bemusement.

She confesses it is hard work, and the returns are very low. Today in particular has been very difficult. She anticipates to earn about one thousand shillings from her catch. The previous day was much better. She made 540 Kenyan Shillings (16,000 Ugandan shillings). She used some of the money to buy food and saved 100 Kenyan Shillings. She now believes the gold has eluded her because of the saving she made. “It is as if it (gold) doesn’t want you to save,” she says.

Chepkararat is a budding gold town, full of life at night, my tour guide tells me. It has been nick-named ‘Dubai’ because of its vibrant life style and gold trade. It is here that gold buyers, both local and from across the border in Kenya, come to buy what the miners have collected for the day. When the transactions are done and money has exchanged hands, the miners indulge in the night life, spending all that they have made or else risk not getting anything at all the following day.

But for women like Grace, it is a matter of life and death. The river bed has fuelled her family’s survival for years as the harsh Karamoja sun leaves her with few options for agriculture. “It is hard work,” she tells me while shaking her head as she returns to the heap of sand next to her to ‘wash’ it for more gold.

As I walk away, I look at my watch and it is 4 PM. I wonder whether the day will get any better for her with nightfall only a few hours away.

Programs Director

Africa Centre for Energy and Mineral Policy (ACEMP)