The narrative on transiting to a low carbon emission energy system has dominated the international developmental agenda, with a number of countries already taking a leading role in planning for this transition through crafting responsive renewable energy policies. As reported by the World Economic Forum, Germany which is the world biggest producer of ignite (dirty grade of coal) intends to phase out coal by 2038. Germany will set up a $45 billion compensation package which will compensate mines and utilities for lost production revenues, fund new infrastructure projects in coal dependent areas and help coal-industry workers retrain for new jobs in their local area. The German government aims to generate at least 65% of the nation’s electricity from renewable sources by 2030 (ibid). Likewise, for China guided by the Energy Production and Consumption Revolution Strategy (2016-2030) by 2030, 50% of total electric power generation will be from non-fossil energy sources, including nuclear and renewable energy.

In 2017, renewable energy encompassed 36.6% of China’s total installed electric power capacity, and 26.4% of total power generation. China ‘s Three Gorges Dam is the largest hydroelectric dam in the world and boasts a generation capacity of 22,500MW. More so by 2017, China’s wind-energy generation increased to 304.6 billion kWh, a 28.5% increase from the previous year. China also leads in solar capacity and according to Wood Mackenzie China’s photovoltaic panel installation hit a cumulative total of 370 GWdc by 2024 – more than double the US’s capacity at that point. According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) In 2018, renewable energy sources accounted for about 11% of total United States energy consumption and about 17% of electricity generation. The consumption of biofuels and other non-hydroelectric renewable energy sources in the United States more than doubled from 2000 to 2018, mainly because of state and federal government requirements and incentives to use renewable energy. Besides, Germany, China and the USA, Denmark also generates more than half its electricity from variable renewable energy sources.

Low Carbon Economy as a Business Opportunity

While climate change presents a huge threat to humankind, it is fundamentally important to note that the transition to a low carbon economy also presents huge global trade and investment opportunities. During 2018 World Economic Forum, Anand Mahindra the chairman of the Mahindra Group aptly stated that “climate change is the next century’s biggest financial and business opportunity. Tracy Wolstencroft (Global Head of Environmental Markets at Goldman Sachs) maintains that “the opportunities before us in clean energy technology offer enormous potential for creating new ways to generate the energy we need, and at the same time create jobs and drive economic growth”. According to a 2017 report by the International Finance Corporation, tackling climate change could unlock a $23trillion investment opportunity by 2030 in emerging markets alone.

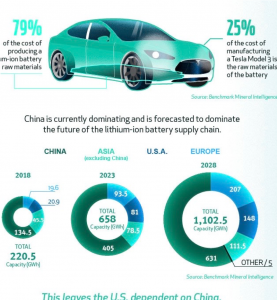

As a result of such investment opportunities climate change presents, nation states and big corporates from China, EU and the USA are in an arms race to control commodity supply chains of energy minerals and ultimately have a huge share in the production and sale of such renewable energy products such as solar PV, wind turbines and electric vehicles. Fabien Vieau who is Google’s EMEA principal for data centre energy and location strategy argues that “what’s happening these days, it’s a competition, it’s a clean energy arms race. Who’s going to purchase the biggest amount of renewable energy. This is good for business, it’s good for the planet so we should enjoy this. The transition towards a low carbon economy has made such energy minerals as lithium, copper, uranium cobalt and manganese to be highly valuable. In actual fact the transition has also birthed a new race, dubbed as the battery race and according to Nicholas LePan (Mining Editor for Visual Capitalist) battery minerals are set to be the new oil and lithium-ion battery supply chain being new pipelines.

According to the Global Battery Alliance, the lithium-ion battery market, which is the strongest growing battery market segment, increased by 15% (CAGR) between 2005 and 2015 and the global battery market is estimated to see continued growth from currently $65 billion to a size of $100 billion by 2025. According to McKinsey, sales of EVs topped one million units in 2017, the market was valued at $106.5 billion in 2016 and is expected to grow by 18% year on year from 2018 to 2023. In 2018, global electric vehicle sales increased by 64% compared to the previous year, causing battery manufacturers to expand battery operations.

According to the Global Battery Alliance, the lithium-ion battery market, which is the strongest growing battery market segment, increased by 15% (CAGR) between 2005 and 2015 and the global battery market is estimated to see continued growth from currently $65 billion to a size of $100 billion by 2025. According to McKinsey, sales of EVs topped one million units in 2017, the market was valued at $106.5 billion in 2016 and is expected to grow by 18% year on year from 2018 to 2023. In 2018, global electric vehicle sales increased by 64% compared to the previous year, causing battery manufacturers to expand battery operations.

The key question then who is bound to benefit from these economic  opportunities brought forth by the transition to a low carbon economy. Between 2013 and 2018, China’s investments in renewables grew from $53.3 billion to an impressive peak of $125 billion. China is the biggest location for renewable energy investment, accounting for more than 45% of the global total in 2017. China accounts for 70% of the global lithium cell manufacturing capacity with the United States at just 12% while Europe accounts for 3% of the global production capacity.

opportunities brought forth by the transition to a low carbon economy. Between 2013 and 2018, China’s investments in renewables grew from $53.3 billion to an impressive peak of $125 billion. China is the biggest location for renewable energy investment, accounting for more than 45% of the global total in 2017. China accounts for 70% of the global lithium cell manufacturing capacity with the United States at just 12% while Europe accounts for 3% of the global production capacity.

The success story of Tesla (an American EV and clean energy company also best illustrates the extent to which the transition to a low carbon economy presents remarkable opportunities for investment and business growth. Tesla’s price per share went from $9 to $443 between 2009 and 2020. It took only 7 years for Tesla to pass Ford and General Motors and at the point of writing, Tesla market capitalization is now about $80 billion more than double that of Ford ‘s, at $37 billion. Tesla’s valuation has already surpassed the $100 billion mark – a significant milestone for a company that produces a fraction of the vehicles of its direct competitors. Such is the value and investment opportunity in the low carbon economy, but the troubling question is, how is Africa responding to such an opportunity.

Africa’s Competitive Advantage in Energy Mineral production

While Africa is a key producer of energy minerals, the continent seems to be blinded to the opportunity energy minerals and the low carbon economy presents. As Tariye Gbadegesin (see the Africa Report of January 2020) states that in 2018, Zimbabwe and Namibia were among the top 10 countries for global lithium production, with Zimbabwe alone holding 11m tonnes of lithium ore in its Bikita mines. South Africa is the world’s largest producer of manganese, a key battery metal, and holds competitive advantage in producing lithium -ion batteries in large quantities. According to the Africa Energy Outlook (2019) the Democratic Republic of the Congo accounts for two-thirds of global cobalt production and South Africa produces 70% of the world’s platinum, which is used in hydrogen fuel cells. Tariye Gbadegesin also notes that graphite exports to China from Africa rose by an impressive 170% in early 2019 due to heightened Chinese demand for the raw material and Tanzania is poised to become a significant graphite producer, with Tanzanian-based Mahenge Resources, receiving two major licenses in February 2019 to proceed with mining projects. The DRC and Zambia are amongst the top 10 copper producers in the world with an annual production of around 1,030,000 tonnes and 708,000 tonnes respectively.

Rethinking Africa ‘s role in Clean Energy Value and Commodity Supply Chain

The Africa Mining Vision provides a framework on how Africa could at least capitalize on economic opportunities the low carbon economy presents. The AMV clearly states the need for a knowledge-driven African mining sector that catalyzes & contributes to the broad-based growth & development of, and is fully integrated into, a single African market through:

- Down-stream linkages into mineral beneficiation and manufacturing;

- Up-stream linkages into mining capital goods, consumables & services industries;

- Side-stream linkages into infrastructure (power, logistics;communications, water) and skills & technology development (HRD and R&D);

- Mutually beneficial partnerships between the state, the private sector, civil society, local communities and other stakeholders; and

- A comprehensive knowledge of its mineral endowment.

The AMV further underscores that Africa’s mining sector should be a major player in vibrant and competitive national, continental and international capital and commodity markets. To get to this level, there is a greater need to rethink Africa ‘s developmental question in this new era of energy transition and come up with a Renewable Energy Strategy for the Continent. Underlying such a strategy should be a firm commitment to the AMV and a common market for the consumption of renewable energy products produced within Africa. Such a strategy should clearly recognize how the low carbon economy could potentially transfer more losses to Africa if the demand for energy minerals is not properly managed.

The demand for energy minerals and increases in commodity prices for these minerals can potentially entrench the enclave economy. More so, the demand of energy minerals and the subsequent increase in their prices can further render African countries to the debt crisis as was the case when a barrel of oil prices increased from $20 in 1999 to more $140 in 2008. As a result of the hike in oil prices and huge dependence on exports, Chad got a loan of $1.4bn from Glencore hoping that the loan was to be repaid with future sales of crude, then trading above $100 a barrel (Mutondoro, 2016). Two years later, as the price dived, debt payments were swallowing 85% of Chad’s dwindling oil revenue and resultantly for weeks, schools were closed and hospitals paralyzed, as workers went on strike against austerity.

There is a greater need for African countries through their Regional bodies, Governments, Parliament, Civil Society and think tanks to revisit their economies policies as such prevailing policies have aided the enclave economy, an economy dependent on rents from export of mineral products in their raw form. Tariye Gbadegesin argues that Africa needs to follow the US and Europe in adopting a forward-thinking policy on battery value-addition. In this blog article I argue that the real economic value in the low carbon economy is not so much into exporting such energy minerals in their raw form but rather controlling the commodity and supply chains of renewable energy products. Africa needs a Renewable energy strategy which clearly outlines the value proposition in the low carbon economy. More importantly, the proposed Renewable Energy strategy needs to consider the risk that the low carbon economy will present to Africa. Some of the key risks to consider include challenges of financing for the low carbon economy, productivity losses as a result of the transition, opportunities for corruption as well as conflict. This can only be possible through futuristic visionary pragmatic leadership, sound policies and massive investment into research and development.

This article was authored by Farai Mutondoro and originally posted on: LINKEDIN