In 2017, under a directive of Uganda’s President Museveni, the Police Minerals Protection Unit (PMPU) was established. At the time, the Unit was created to respond to a growing concern that the country’s mining sector was not properly supervised and needed an enforcer to support the work of the Directorate of Geological Survey and Mines (DGSM).

According to then Police Spokesperson, Asan Kasingye, the Unit was created to “handle issues such as illegal mining, unsafe mining methods and environmental protection.” The Inspector General of Police at the time, Gen. Kale Kaihura, appointed Jessica Keigomba, formerly the Interpol Liaison Officer at Entebbe Airport, as the first PMPU Commandant. A statement released by his office outlined the roles of the PMPU to include implementation of plans, policies and strategies for effective security of minerals in the country and conducting inspections surveillance and monitoring in order to detect and prevent illegal mining in the country.

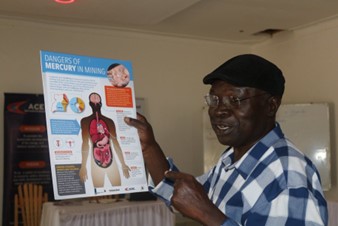

Industry insiders were quick to point out that the Unit’s roles had glaring similarities to those of the DGSM and expressed their concern on introducing armed people in Uganda’s mines. “You can not have guns in mines,” Don Binyina from the Africa Centre for Energy and Mineral Policy (ACEMP) said at the time. “The moment a serious investor sees any armed personnel at a mine site, they will never risk their money there.” Mr. Binyina, then Chairperson of the ICGLR Mineral Audit Committee, was worried that deployment of the PMPU in Uganda’s mines, particularly those producing conflict minerals (Tin, Tantalum, Tungsten and Gold) would be negatively interpreted by the industry which was increasingly speaking against State and Non-State armed groups in mining areas in the Great Lakes Region, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Two years later, there are mixed feelings within the mining communities in Uganda regarding the work of the PMPU. Three incidents in particular have cast the Unit’s work in bad light and cast doubt on their mandate in Uganda’s mining sector. This three-part article focuses on only the first incident: The controversial Mubende gold mines evictions.

Black August

The first incident is the controversial eviction of artisanal miners from Mubende in August 2017. The evictions were conducted jointly by both the national army (UPDF) and PMPU acting on the directives of the President of Uganda. Approximately seventy thousand people who included miners, workers and family members were given two hours to vacate their mines and homes within the mining camps. Property was destroyed, machinery confiscated, and livelihoods lost. That eviction, however devastating to the victims, is not the focus of this article. The events that followed are.

According to residents in that area, following the evictions, personnel of the PMPU took over mining operations and are indeed mining up to this day. Initially, some of the evicted artisanal miners who, possibly because they did not have anywhere else to go, were lurking around the trading centres in close proximity of the cleared area, started approaching some members of the PMPU to allow them to access their former mines in exchange for a cut from their earnings. For weeks, these artisanal miners accessed those areas in the cover of darkness and duly shared their loot with some members of the PMPU. Later, reports emerged that some members of the PMPU had started mining for themselves.

In one of our visits late last year to what was formerly called the Lujinji camp in Mubende’s Kitumbi Sub-County, there was no visible sign of day-time mining activity. Overgrown grass surrounded the PMPU outpost. Visitors were not allowed beyond the outpost into the former mining areas. Within the one hour that this writer spent at the PMPU, a motorcycle or two carrying about four 20 litre jerricans of water would occasionally pass by unchecked and head into the mining areas only to return with empty jerrycans. The motorcycles made at least 3 trips in that hour.

Despite being denied access into the mining areas, we chanced upon some artisanal miners brave enough to talk about their ordeal. One of them, names withheld, stayed in Mubende for six months after the evictions before he called it quits. The PMPU charged him five million shillings every week to mine. He was lucky though and within two weeks had drilled up to 40 feet and hit a 400-gram deposit of gold, another 200 grams and then 100 grams followed in a few days. He sold all the 700 grams at eighty million shillings. The landlord, seeing how much this miner was making, increased the fee for use of his land to seven million shillings every week. This wasn’t feasible as the miner was already paying the PMPU five million. He decided to move to another plot and dug into another pit, still paying the PMPU. This pit however did not yield as the first one did. Within a few weeks of paying the PMPU and yielding nothing from the mines, the eighty million shillings had vanished.

Having run out of money, he decided to move to Kaabong where some of his mining colleagues had relocated after the evictions. Three months into Kaabong, he says he heard that the PMPU in Mubende had reduced their weekly charge to three million due to complaints from the miners. He had no plans of returning there though, because the only payment he was currently making from his income was to the landlord.

In the second part of this series, we shall bring you more incidents that have led many in mining circles to baptise the PMPU as the ‘Mining Police of Uganda.’

Programs Officer,

Africa Centre for Energy and Mineral Policy (ACEMP)