Deep inside Rwemizi village in Ruhama Parish, Ntungamo district a group of miners have resolved to keep the tin they mine until they are able to get a processing centre to add value and be able to fetch better prices.

While they say the resolution is voluntary, it appears to have been forced unto them by the poor prices offered by the buyers that come to them.

But while other miners chose to keep selling at that poor price, according to Ipolito Kinyata, the chairman Rwengoma Artisanal and Small Scale Miners Association, his group has bigger ambitions.

And things are already looking up, Kinyata says. Funders from Australia have promised to establish for them a processing centre so that their tin leaves the site as a finished product.

“We want to add value,” Kinyata says, “The way we sell now, there is no market. Whoever comes to buy offers a poor price. You find that the price is UGX60,000 a tonne of tin on the world market but here you are only given UGX 15,000 or UGX 20,000. The reason we fetch these poor prices is because of the waste that goes with our tin.”

He explains that his group started out small but now boasts of 30 people working on the same mine. Majority are women. The group is a partnership between Rwengoma Artisanal and Small Scale Miners and Ntungamo Tin Dealers.

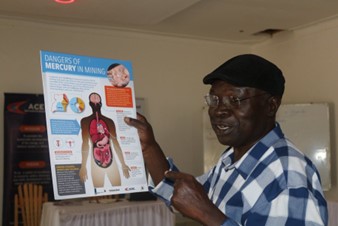

Kinyata says that owing to their organisation, the African Centre for Energy and Mineral Policy (ACEMP) identified them, offered them a lot of training here, in Kampala and others were taken to Kigali for training and gave them protective gear.

When we arrive at their mine, about ten of them are donning blue overalls, white gumboots and plastic caps.

“They also helped put us in touch with a company called Hills Resources,” Kinyata says, “We did not have a licence and were operating

like bees without a queen. Hills Resources helped get us get a licence.”

Kinyata says that they are now focussed on mining more volumes of tin but are still held back by lack of equipment. To get the tin, they dig narrow tunnels because they use our bare hands and hammers. Inside the mine they have encountered hard rocks, which require explosives to break them.

“We should be having jack hammers or makitas,” Kinyata says, “But we haven’t reached that level.”

Despite that Kinyata’s association has ambitions to be a leading example in the whole country and world over.

“We call upon all those who can come in and assist us because the more we develop, the more our village will develop and once the village develops, the country develops and once the country develops, the world also develops,” Kinyata said with a green as he bid us farewell.